I’d already written one song for a movie. Somebody in Nashville—Cathi King or Eugene Epperson or Dixie Gamble—had given me the screenplay for Fresh Horses, a Molly Ringwald and Andrew McCarthy vehicle from the late 1980s. I went for the brass ring and wrote a song called “Fresh Horses,” which was probably both an arrogant and a naïve thing to do—to go for the title song on the soundtrack.

I recorded a demo and submitted it to whichever person asked for it, who passed on to some contact they knew who was working on the project.

No response returned from the void. Without deciding the arrogance-or- naïveté question, I chalked it up to experience—Don’t go for the title song!

I liked “Fresh Horses” regardless, so I added it to my band’s set list and moved on.

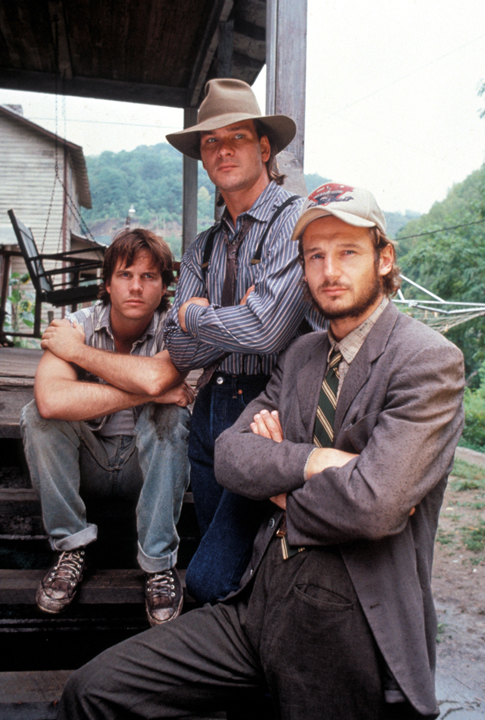

A year or so later, Dixie, who was serving as my manager at the time, handed me another screenplay and asked me to write a song for it. Next of Kin had the potential to be a box-office powerhouse, featuring Patrick Swayze, Liam Neeson, Bill Paxton, Helen Hunt, and Ben Stiller, who also happened to be in Fresh Horses.

The Next of Kin screenplay told the story of three Gates brothers from eastern Kentucky coal country. In order of age they are Briar (Neeson), Virgil (Swayze), and Gerald (Paxton). Briar owns a coal truck and takes pride in the work he does for this local industry. Virgil has migrated to Chicago, where he has married Jessie (Hunt) and become a cop; his beat is Chicago’s hillbilly slums, where he knows the people and speaks the language. Briar and Virgil struggle in a tug-of-war over the future—and soul—of Gerald, the baby of the family. For his part, Gerald tries to pacify both of his older brothers; he moves to Chicago to work, intending to stay only long enough to save the money to buy his own coal truck. He gets a job delivering pinball machines and other games to restaurants, bars, and arcades. The business is, of course, owned by the mafia, and Gerald’s upstanding morals in defending a job and property he believes to be on the up-and-up soon get him killed.

When Virgil returns Gerald’s body to eastern Kentucky for burial, he and Briar fight about justice for baby brother. Virgil begs his family’s patience with the law and its processes, but Briar wants an immediate hillbilly reckoning. After Virgil returns to pursue his investigation, Briar—driving something like a rusted 1939 Chevrolet Half-Ton—sneaks into the Windy City to begin an investigation on his own terms, in the course of which he, too, dies at the hands of the mob.

Virgil then decides Briar’s path is the way to go. He turns in his badge and summons up from southern Appalachia a group of bird-call-communicating, bow-and-arrow-wielding, school-bus-full-of-snakes-driving mountain men to help. The story’s Armageddon takes place at night in a sprawling Chicago cemetery.

The screenplay ended without any dialogue I can remember, only the description of a scene. The camera hovers just outside the rear window of a vehicle, with Virgil at the wheel and Jessie in the seat beside him. Ahead, seen through the front windshield, is a straight, two-lane highway, running through flatland. Then the camera begins to rise, and as the vehicle moves ahead, we see that it’s Briar’s old pick-up. And then we see Briar’s coffin in the truck bed and the hazy outline of the Appalachian mountains—“home”—in the blue distance.

Homecoming, I thought.

Sitting at the kitchen table with my Guild six-string acoustic across my lap and a handful of open, droning chords in the key of E (E, A, B, C#m), I began to hum a bit of pentatonic melody. The first verse spilled across the page pretty quickly and easily:

If I die in this place so far from home

And I never make my living from my native soil again,

Don’t leave me where these strangers will walk across my bones.

Take me back and lay me with my next of kin.

I couldn’t help it. While I’d learned my lesson about not giving the film’s title to my song, I couldn’t help but slip this second film’s title into the first verse. It just worked.

But then I began to lose the plot, as far as the screenplay went, and my own circumstances and experiences took over.

I’d been living in Nashville since the early 1980s, almost a decade when the Next of Kin screenplay came my way. Plenty of great friends, small successes, and good times had come my way during those years. I’d developed into what I thought was a good songwriter, and I had a great band that seemed beginning to build a little bit of a following. But running parallel with these were significant disappointments—I don’t want to call them failures, even though they might have been. Among these were two major studio albums that were recorded but never released, and major label interest in the band and me that never quite came to fruition. I turned thirty years old in 1988, a milestone for thinking, for reassessing, and I was considering leaving Nashville and going home. My songs from that time suggest that this was on my mind a lot: “Best I’ve Ever Seen,” “There Was Always a Train,” and “Genesis Road,” to name a few.

Two things happened to decide my fate: first, I read the ending to the Next of Kin screenplay and wrote “Homecoming,” turning my eyes toward home in the mountains of western North Carolina, and second, Leesa came back into my life.

After the first verse of “Homecoming,” quoted above, the rest of the song—chorus, a second verse, a bridge—kept loosely to the spirit of the screenplay but more particularly began to express my own feelings. Maybe that’s why the song made it to the last cut (or so I heard) in the filmmakers’ selection process but ultimately didn’t make it into the film. (Another possibility—contributing at least—is the fact that the film didn’t include the screenplay’s ending, for which I wrote the song. Rather than the beautiful highway scene described above, the film ended with Virgil going back to his police chief’s office, getting badge, and meeting Jessie outside on the sidewalk. As it turned out, the film was never the powerhouse it had potential to be.) I’m okay with the song’s not making the final cut—at least I’m over the disappointment. As with “Fresh Horses,” I’m glad to have written “Homecoming.”

But it’s more than being happy to have written in the case of this one. I’ve often said that—“gun to my head”—I would name “Homecoming” as my favorite among the many songs I’ve written.

Homecoming

If I die in this place so far from home

And I never make my living from my native soil again,

Don’t leave me where these strangers will walk across my bones.

Take me back and lay me with my next of kin.

There were many things my father could not say.

He turned the sod and swung the rod and kept his feelings locked inside.

When things around the homeplace went from bad to worse to stay,

He sat in silence with my brother as I said good-bye.

Homecoming dreams are bittersweet to the taste.

Homecoming promises are hope to the displaced.

They echo through my soul with the distant music of “Amazing Grace.”

Let there be a homecoming some day.

I have learned to breathe beneath this sea of light.

I’ve won and lost and paid the cost to find a future for myself.

But the ties of blood and earth still bind across the years and the miles,

And in my memories the old ways still are dearly held.

Homecoming dreams are bittersweet to the taste.

Homecoming promises are hope to the displaced.

They echo through my soul with the distant music of “Amazing Grace.”

Let there be a homecoming some day.

I’ve been cursed as a deserter and prayed for like a prodigal son.

Seems no matter where I’ve turned, my loyalties have fallen under the gun.

Homecoming dreams are bittersweet to the taste.

Homecoming promises are hope to the displaced.

They echo through my soul with the distant music of “Amazing Grace.”

Let there be a homecoming some day.

There’ll be a homecoming some day.

Postscript: My songwriting practice tends toward the solitary. Nashville—Music Row—was a place of cowriting, with at least two but often three or four songwriters credited on each tune in the Billboard “Hot Country Songs.” (Even as I write this over thirty years later, this week’s number one country song—“The Kind of Love We Make” by Luke Combs—lists four, maybe even five, songwriters.)

I hope to write a monthly Song Stories post for every third Saturday. If anybody reads this and would like to request that I write about a particular song, please feel free to contact me (michaelamoscody@gmail.com).