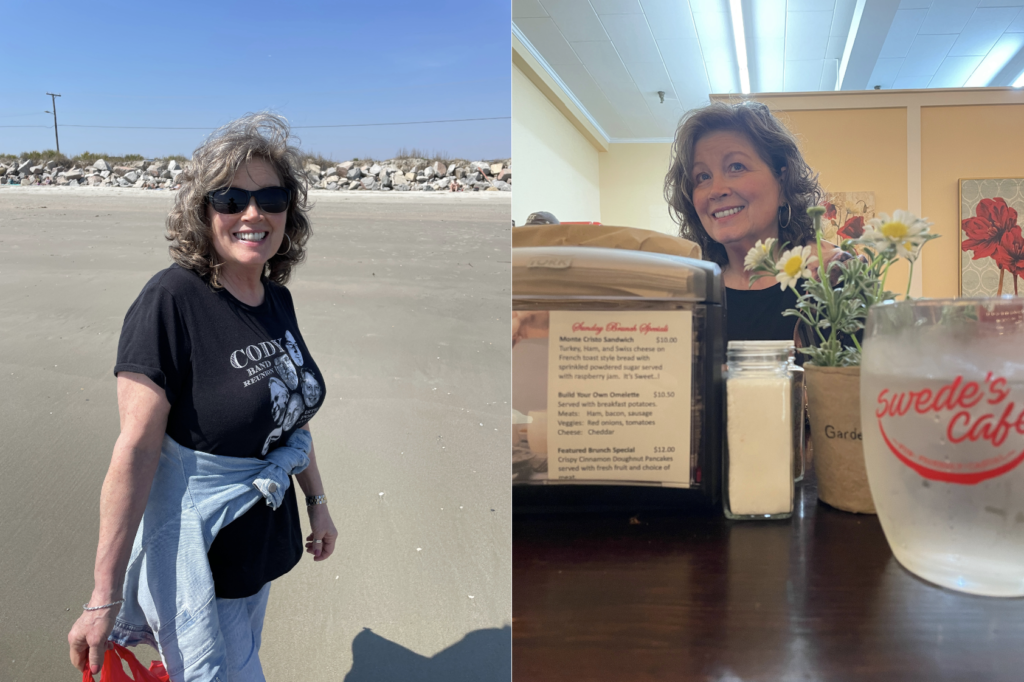

Back in 2014, Leesa and I traveled with a group of friends to Vimperk, a small town in the southwestern portion of the Czech Republic (aka Czechia). A bunch of us lived for a week in a hostel on Vimperk’s beautiful cobblestone square. At least that’s where we slept. During the day, we were on the run, offering a softball camp for youth and English camp for adults. In the evenings, we did a good bit of sightseeing.

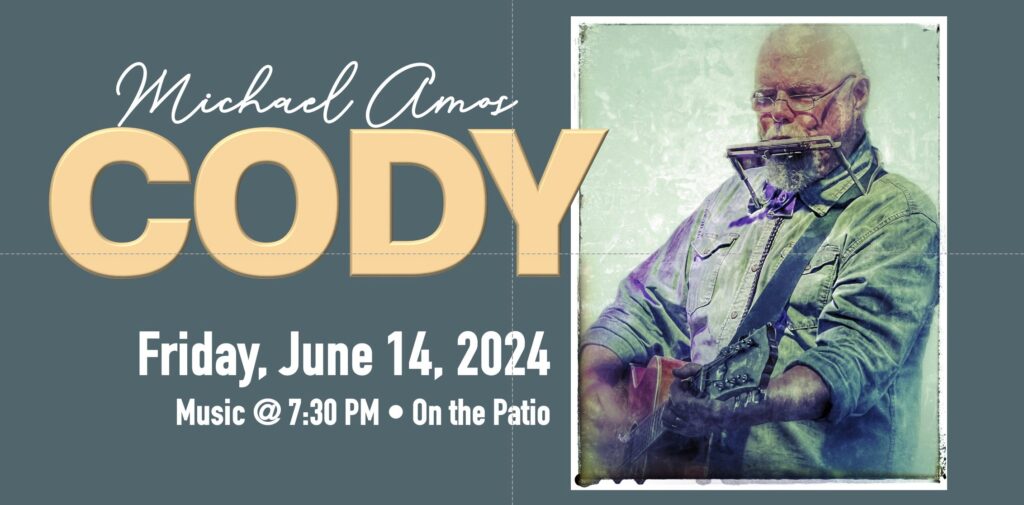

In the middle of that week, I played a concert for the town. We found advertisements for this event scattered around Vimperk when we arrived.

It was a terrific experience all around.

In 2015, Leesa and I decided—for a number of reasons—not to go back, but we really missed the place and the people and turned our eyes toward 2016. Meantime, I began to think about a song for Vimperk.

One of the surprising things about that 2014 trip came in the form of good sleep. I’m a white-noise sleeper. I keep a fan running beside the bed every night, not for the breeze but for the steady sound of it. Not only would the hostel where we slept be without a steady hum to lull me to sleep, but also there were bells. Bells, bells, bells all through the night. The clock tower in the square rings its bells every fifteen minutes—one bell for the quarter hour, two for the half, three for a quarter ’til, four for the hour with these last followed by the deeper, louder bell tolling the hour itself. I couldn’t very well pack a fan for the trip, so I bought some melatonin and hoped for the best.

But it wasn’t long before something—the Old-World ambiance; tiredness from travel and engaging with the Czechs (young and not so young); running to take in the sights; something—lulled me to sleep and gave me a good night’s rest every night. Sure, I was to some degree roused from sleep every quarter hour, but rather than being annoyed at the interruption or unable to get back to sleep, I felt a distinct sense of peace and comfort from lying down to rising up.

During 2015, when I both wanted to write a song for Vimperk and knew, at the same time, I couldn’t go back that year, the image of those bells became the spark that lit my way into the lyric.

The bells of Vimperk ring the quarter hour through the night.

Hear their voices on the air!

And the bells of Vimperk sing that everything’s all right—sleep tight.

All is well down in the square . . . and quite like a prayer.

That’s where the song started.

I’m not going to write much here about what went into the two verses. Suffice to say that they contrast the two worlds as I thought about them at that moment. The first verse is set somewhere like Johnson City or Asheville or Nashville, the second in Vimperk. You should be able to figure out my feelings about these contrasting cultural experiences.

This is a noisy world that clamors for my short attention—

Talking heads that blather on and on and on.

The streets are filled with sirens—some real and some legendary—

From the setting to the rising of the sun.

Come Friday night the bars are loud and crowded with the lonely,

Seeking some attention or some means of escape.

I leave my car downtown and take a taxi home,

Where stone awake my mind drifts half a world away.

The bells of Vimperk . . .

So, that’s the first verse. Here’s the second.

Music echoes through the sunlit streets of cobblestone.

It’s “Country Roads” by an accordion band.

And the old men on the stage hold lovers in their laps and squeeze them,

Making the music everyone can understand.

Come Friday night the pub’s alive with flutes and fiddles and guitars

That long past midnight fade to soft lullabies,

Sung in harmonies that carry me home,

Where warm and weary I lie down and close my eyes.

The bells of Vimperk . . .

I was told at the beginning of the 2014 trip that many Czechs love John Denver’s “Country Roads.” (Actually, I learned many years later that they prefer a Czech version from one of their own singers.) When we first arrived at the door of our hostel on the cobblestone square, a small festival of some sort festival was happening. On a stage beneath the clock tower, an accordion band was playing—can you believe it?—”Country Roads”!

To the bridge!

The world is older there,

But it’s somehow younger, too.

When the ground beneath my feet is shaken,

I go there and find my faith renewed.

The bells of Vimperk . . .

The bridge of the song tries to feel its way to an idea I find difficult to express. Vimperk has been there in hills so much like our own for more than twice the lifetime of the U.S. In 2014, our final team meal was at a home on a hill above Vimperk. The house itself was as old as the US. Pictured below, the Black Gate on the hillside beneath the castle was built in 1479, which is a century and a half before the Puritan Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts Bay to establish Plymouth Plantation (1620).

I feel certain that the place’s feeling younger (while being so much older) has to do with a number of things. First, I’m sure those of us who love Vimperk and the people we know there tend to romanticize its Old-World beauty, the slower pace of a small town, the foreignness and yet familiarity of it, a kind of fairytale quality that radiates from its castle and cobblestones and surrounding forests. We don’t see the drugs, which are surely there. We don’t see much if any of the poverty, which is surely there. We don’t see much of its prejudices—against the Roma (so-called “Gypsies”), for example. We don’t see much of the ignorance and meanness and violence that are surely there as well—I mean, come on, they’re mostly igno-arrogant white people like us, aggressive and colonizing in both large (global) and small (local) ways.

What we do sometimes see, however, at least among most of those we come in contact with, is a way of relating to one another that often seems lost here. One quick example: in the softball camp setting, an atmosphere of caring for each other and cooperating with each other is evident. Rarely here in the U.S. would you see teens willing to play with the little kids without being made to do so. That happens all the time at camp without any teen tantrums. At lunch, you’ll find tables made of up teens who are sitting and eating with kids much younger than themselves.

So, anyway, Leesa and I returned to Vimperk in 2016, and I performed another concert and enjoyed the opportunity to play “The Bells of Vimperk” for our friends in Vimperk. Below is a phone video of that performance.

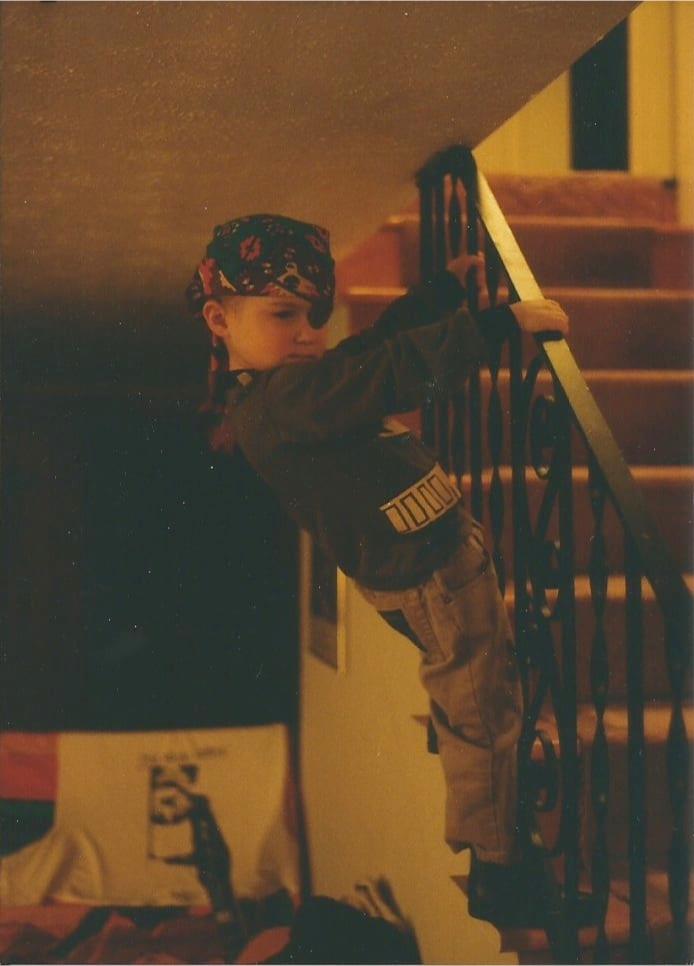

Recently I played a backyard concert at the Barnett Patio here in Johnson City, and my son Raleigh sat in on bass (along with my friend Jimmy on percussion). I don’t know if Raleigh had ever even heard “The Bells of Vimperk,” but at the end of the night, he said, “Deddy, that might be your best song.” I’ll take that!

This is a noisy world that clamors for my short attention—

Talking heads that blather on and on and on.

The streets are filled with sirens—some real and some legendary—

From the setting to the rising of the sun.

Come Friday night the bars are loud and crowded with the lonely,

Seeking some attention or some means of escape.

I leave my car downtown and take a taxi home,

Where stone awake my mind drifts half a world away.

The bells of Vimperk ring the quarter hour through the night.

Hear their voices on the air!

And the bells of Vimperk sing that everything’s all right—sleep tight.

All is well down in the square . . . and quite like a prayer.

Music echoes through the sunlit streets of cobblestone.

It’s “Country Roads” by an accordion band.

And the old men no the stage hold lovers in their laps and squeeze them,

Making the music everyone can understand.

Come Friday night the pub’s alive with flutes and fiddles and guitars

That long past midnight fade to soft lullabies,

Sung in harmonies that carry me home,

Where warm and weary I lie down and close my eyes.

The bells of Vimperk ring the quarter hour through the night.

Hear their voices on the air!

And the bells of Vimperk sing that everything’s all right—sleep tight.

All is well down in the square . . . and quite like a prayer.

The world is older there,

But it’s somehow younger, too.

When the ground beneath my feet is shaken,

I go there and find my faith renewed.

The bells of Vimperk ring the quarter hour through the night.

Hear their voices on the air!

And the bells of Vimperk sing that everything’s all right—sleep tight.

All is well down in the square . . . and quite like a prayer.