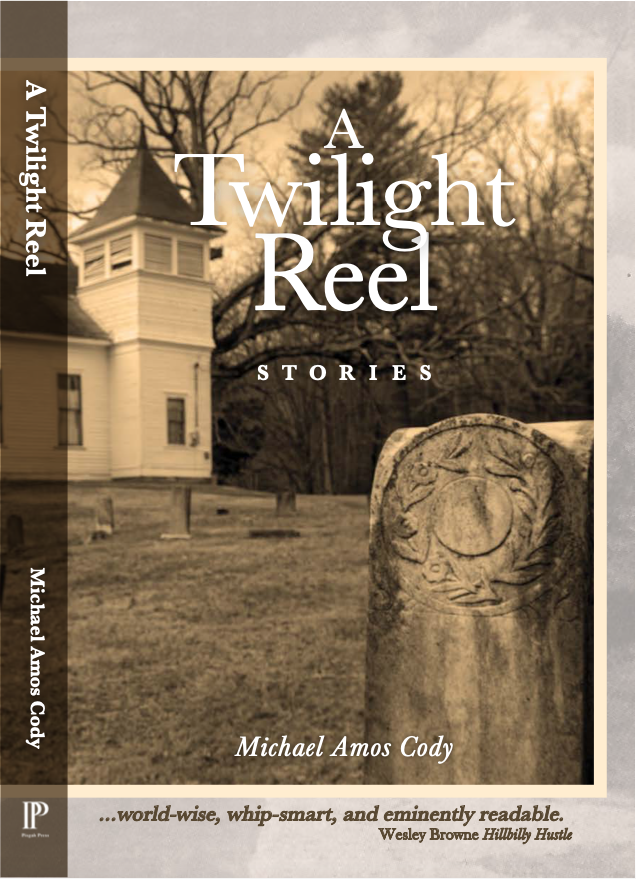

My new book, A Twilight Reel: Stories, is set for publication on May 25 by Pisgah Press in Asheville, NC. The collection is made up of twelve stories, each set in a different month of 1999. The physical setting for all is my imagined town of Runion, North Carolina, which is on the French Broad River between Marshall and Hot Springs in Madison County.

Here’s a list of the stories included:

- The Wine of Astonishment

- The Loves of Misty Sprinkle

- Overwinter

- The Flutist

- Decoration Day

- Conversion

- The Invisible World around Them

- Grist for the Mill

- A Poster of Marilyn Monroe

- A Fiddle and a Twilight Reel

- Two Floors above the Dead

- Witness Tree

I thought I’d share some writing I did a few years ago about the setting, the use of place, in these stories.

When “place” is mentioned in relation to fiction, the first thing that comes to mind is physical setting. This is the world of the story. It may be anything from a solitary room to an overcrowded neighborhood, from Yoknapatawpha, Mississippi, to “dear dirty Dublin.” If the fiction is fully realized, we as readers will be able to enter this world, to see its colors and shapes, to hear its noises and silences, to smell its aromas and stenches, to feel its textures.

However, a sense of place in fiction is not achieved by the depiction of a physical setting only–its topography and wildlife and climate, its antebellum homes and filthy streets and glittering skyscrapers. There is a spiritual element to setting that is not inherent in the place itself but rather exists according to human experience of the place: an experience built up over time with thick layers of cultural, communal, familial, and individual histories.

I have chosen to place the following four stories in the environs of the fictional Appalachian town of Runion, North Carolina, “my own little postage stamp of native soil.” Appalachia is, I believe, a fertile subject for fiction that remains far from being exhausted. Jim Wayne Miller, a poet native to mountains not far from my Runion, says, “the Appalachian region of America, being neither north nor south exactly, neither east nor west, but a geographical, historical, cultural, and spiritual borderland, has an interesting and complicated past (and present)” (86). This quote implies that even though North Carolina may be considered part of the same “South” as Faulkner’s Mississippi, there is a sense that life in its western mountains is something other than life in what is traditionally known as “the South.” In fact, the spirit of the place, especially that of the more sparsely populated areas like Madison County (where I grew up and where I locate Runion), seems to make it as much the southern region of what some have imaginatively tried to create as “the state of Appalachia” as it is the western region of North Carolina. [Jim Wayne Miller was born in Leicester, NC, although he spent much of his creative life in Kentucky. Also, at the time I wrote this, I think I was unaware of the early American proposal for an actual State of Franklin that would have included at least some of western North Carolina.]

The idea that Runion is a part of some borderland has colored my intentions in writing all of these stories. In addition, I have sensed in Runion the “interesting and complicated past (and present)” to which Miller above refers. All of the stories are set in contemporary Runion (the late 1980s, the early 1990s). This time of stressful change–when the portions of mountain culture not capable of being made “quaint” for tourists are being absorbed into the world at large–highlights the lines of difference between generations and individuals as well as within generations and individuals. The conflicts that necessarily arise in such a situation are what the stories included here attempt to portray. [By the time I completed the collection, its twelve stories had settled into a single year: 1999.]

It was once upon a time in the Appalachian mountains that accents could change from hollow to hollow and hill to hill. Once, the answer to the question “‘Whose boy are you?’ coupled with the name of the branch on which one lived was sufficient to give one a sense of person” (Sprague 23). And again, a person born in this county or that remained a native of that place no matter how much of his or her life was spent elsewhere.

All that is changing. Life in Appalachia is slowly moving from its traditional isolated state to a backwoods version of the global community. For example, satellite dishes pimple the hillsides behind weatherbeaten mobile homes. They stand among the mossy gravestones of hilltop family cemeteries, eyeing the heavens. They perch on the ridgepoles of dusty barns. They function as a sign that the isolation of the past is being stripped away, and along with it the traditions which it nurtured and preserved.

My purpose in writing these stories is to attempt to capture in fiction some portion of this far-reaching transition. As the older generations try to hold on to what their world used to be, the younger generations are trying to transform that world or escape from it altogether. Those generations in the middle simply seem lost. Connected to the old and attracted by the new, they either freeze and wait for what is coming or run to meet they know not what. The conflicts that exist among all these generations are the stuff of which stories are made, and it is my hope that I am able to write some of the “true” stories taking place among the hills and hollows and communities that surround my fictional Runion.

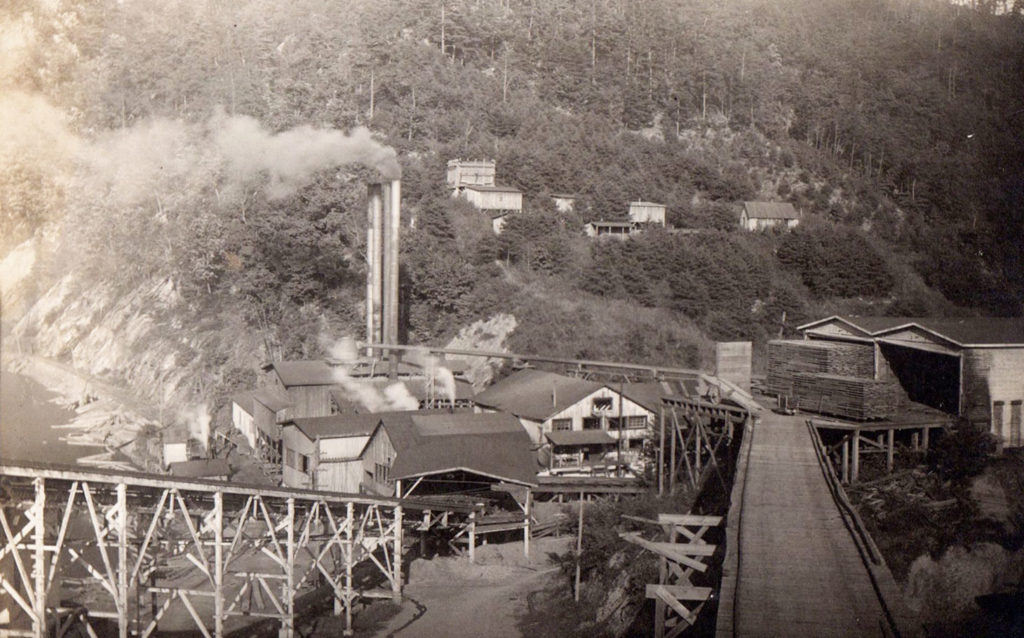

Such fertile fictional ground is incredibly attractive for a writer who feels strongly toward the real ground upon which it is based. In the early part of this century, the actual town of Runion hung on a hillside above the French Broad River between Marshall and Hot Springs in Madison County. A sawmill town of over sixty houses, it died when the mill shut down with the rest of the country in the early 1930s. Today some scattered concrete foundations, the ruins of a one-room wooden schoolhouse, and a single line of jonquils blooming in what once was somebody’s yard are all that remain of Runion. This collection attempts to recreate Runion as if it had never faded out of reality, piecing it together with certain characteristics of the real Madison County towns that surround it–the river town personalities of Hot Springs and Marshall, the small college town atmosphere of Mars Hill–as well as other places that are better labeled villages or hamlets. I realize that four stories cannot create a complete town–Anderson gave twenty-two to Winesburg, Joyce fifteen to Dublin–but I feel I have made a good start.

Place is the basic point of reference upon which the stories in this collection are built. Every layered aspect of each story is affected by it; the fictional modes of “conflict, symbol, tone, style, etc., are all intimately related to Place and mutually interpenetrated” in a “unity” that “can only be intuitively grasped” (Foster 76). The experience of these characters and their stories would not be the same–in fact might not exist at all–without Runion. However, as Leonard Lutwack says in The Role of Place in Literature, “the qualities of [Place] are determined by the subjective responses of people according to their cultural heritage, sex, occupation, and personal predicament” (35). Thus, Runion would not exist without the characters and their stories; they are its living elements, defining its qualities and making it visible.

In his poem “Anecdote of Men by the Thousand,” Wallace Stevens writes,

There are men whose words

Are as natural sounds

Of their places

As the cackle of toucans

In the place of toucans. (51-52)

Stevens concludes with these lines:

The dress of a woman of Lhassa,

In its place,

Is an invisible element of that place

Made visible. (52)

It is the people of a place that make this invisible spiritual element visible: their language, the interconnected colors and themes of their lives that are the visible manifestations of that place. Consequently, it seems to me that fiction attempting to take these invisible elements and make them visible for us as readers must necessarily be fiction of the place as opposed to fiction about the place. It is the fiction of Runion and of an Appalachia-in-transition that I have attempted to create in these stories.

Works Cited

- Foster, Ruel E. “Sense of Place in James Still’s River of Earth.” Sense of Place in Appalachia. Ed. S. Mont Whitson. Morehead: Office of Regional Development Studies, Morehead State University, 1988. 68-80.

- Lutwack, Leonard. The Role of Place in Literature. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1984.

- Miller, Jim Wayne. “I Have a Place.” Sense of Place in Appalachia. Ed. S. Mont Whitson. Morehead: Office of Regional Development Studies, Morehead State University, 1988. 81-99.

- Sprague, Stuart S. “Inside Appalachia: Familiar Land and Ordinary People.” Sense of Place in Appalachia. Ed. S. Mont Whitson. Morehead: Office of Regional Development Studies, Morehead State University, 1988. 20-26.

- Stevens, Wallace. The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens. New York: Knopf, 1954. New York: Vintage-Random, 1990. 51-52.