As I recall . . .

It was in the spring of 1988, and I was writing songs for Ave Canora, a small publishing venture that was part of the music empire of Nashville/Broadway singing star Gary Morris. Word ran through the offices of Gary Morris Music that he would be recording a Christmas album in the near future. I’d never written a Christmas song before, but I really wanted to have a song on that album.

So, in April 1988, in the midst of that year’s Easter season, I sat down to write “Christmastime.” My main musical influences were only two: almost 30 years of hymns and carols in my little mountain church and community in Walnut, North Carolina, and Johnny Mathis’s album Merry Christmas, the Christmas album of all Christmas albums as far as I’m concerned, released in October 1958, less than two months before I was born. I was writing a lot of songs in the key of E at the time, and so, E it was for “Christmastime.”

Here’s an early recording of “Christmastime” from the home studio of my friend Mark Chesshir. It’s possible that this is the demo that I turned in to Ave Canora and the version that Gary heard.

Verse #1 is all about light, which is one of my true loves in the Christmas season. Leesa and I don’t decorate the exterior of our house, but I love the lights of Christmas. Light designs and displays–from simple to complex–are the only thing I enjoy about the extended Christmas season the Xian world developed due to the demands of capitalism.

See the world

In a different light

At Christmastime.

See it shine

In the children’s eyes

At Christmastime.

Let the season sparkle in me

Like the moon on virgin snow

Fallen some long-ago

Christmastime.

We have light appearing in “shine” and “sparkle,” and we have “light” in its different connotation of understanding–to see the world in a different light. Many of us give the world a little more grace at Christmastime. Or maybe we express a little bit of righteous anger at the commercialism that isn’t as much in our faces as at other times of the year. With “virgin,” the lyric includes just a taste, an essence, a foreshadowing, of the Christian story of the birth of Jesus. And the “snow” is classic in terms of memory and desire, for me, as I’m always “dreaming of a white Christmas.”

Verse #2 is about memory. The older I get, the more precious and haunting memory becomes, perhaps especially in the context of Christmas. So much of the celebration and so many of the people I’ve celebrated with are yearly lost and fade into memory.

Window pane–

Watching a parade

Through frosty lines.

Memories–

Bittersweet and homemade–

Cross my mind.

Family and friends at the door–

With the laughter and the kisses pour

Love and good wishes for

Christmastime.

This verse is made up of images from memory. These memories, however, are only implied. They’re left vague and general so that the listener (reader) can plug in their specific memories and memory images. I doubt if I thought that at the time I was writing this lyric, but it’s the way I understand it now.

Verse #3 returns to the Christmas story a bit more directly than the intimation of “virgin” in the first verse. We have a star and a child, a call for peace and stillness, a sounds of celebrating bells and singing people and angels.

Distant star,

I am not alone

With you in sight.

In my heart,

There’s a little child

Alive tonight.

So, let the world lie peaceful and still

While the bells ring and people sing

And angel wings are whispering,

“It’s Christmastime.”

I hope that I got chills, that I maybe even cried, when I completed this last verse. It’s all there, I think, all that Christmas has been to me–all that I struggle to have it still be to me. The star that guided the wise men guides me to the child that is still alive in me. The moon on virgin snow exists as part of a world lying peaceful and still. The parade, the laughter, kisses, and good wishes are echoed in the ringing bells and the singing people. And at the end, the lyric returns one last time to the original Christmas story of angels–the “heavenly host”–appearing to the shepherds.

Here’s “Christmastime” as performed by the Cody band at this time of year back in the day. And here’s the whole lyric together:

Christmastime

See the world

In a different light

At Christmastime.

See it shine

In the children’s eyes

At Christmastime.

Let the season sparkle in me

Like the moon on virgin snow

Fallen some long-ago

Christmastime.

Window pane–

Watching a parade

Through frosty lines.

Memories–

Bittersweet and homemade–

Cross my mind.

Family and friends at the door–

With the laughter and the kisses pour

Love and good wishes for

Christmastime.

Distant star,

I am not alone

With you in sight.

In my heart,

There’s a little child

Alive tonight.

So, let the world lie peaceful and still

While the bells ring and people sing

And angel wings are whispering,

“It’s Christmastime.”

Many thanks to everybody who, over the years, has said that it’s not really Christmas until they’ve heard “Christmastime”!

“Merry Christmas to all!”

Here’s some more stuff:

I’ll go ahead and say it (with some regret and bitterness, and with apologies for the latter): I have a crass commercial desire that many singers had recorded “Christmas Time” so that I could have a nice little royalty bonus every year . . . and so could Leesa when I’m gone . . . and so could Lane and Raleigh when Leesa’s gone. . . .

When I first moved to Johnson City, people used to say, “Hey, I heard ‘Christmas Time’ in K-Mart today!” I even heard it there a time or two myself. But, you know, K-Mart’s not around anymore. (There’s the bitterness again, and again, I apologize.)

Jimmy Patterson was a fellow I met years ago when Leesa, Raleigh, and I attended Cherokee United Methodist Church. He loved “Christmastime.” I heard it told that the first time I played it at Cherokee, Jimmy was standing with our pastor David Woody, and in his excitement over what he was hearing, Jimmy took Pastor Woody’s hand and squeezed it. I don’t know if that’s true, but I do know that “Christmastime” meant so much to Jimmy that his wife Bonnie asked me to play it at his funeral / celebration of life . . . in the summertime, as I recall.

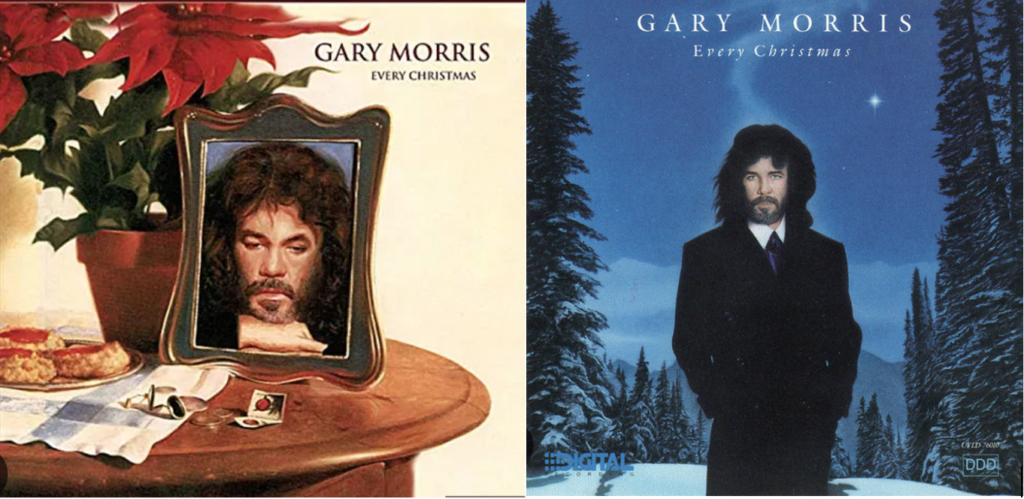

One last thing: Gary Morris released two different versions of his album Every Christmas.

I don’t remember exactly why this was the case, but here’s my story about it. He already had the original Every Christmas album recorded and turned in to Warner Brothers Records by the time I submitted “Christmastime.” That’s the cover on the left, released in 1988. The last song–track 10 on that one–was Gary’s version of “Carol of the Bells.” Then at some point soon afterwards, no later than Christmas 1990, they repackaged and rereleased the album–new cover (on the right) and “Christmastime” replaced “Carol of the Bells.” In practical terms, just as far as publishing goes, Gary’s company would receive what was called mechanical royalties for “Christmastime” that he wouldn’t receive for “Carol of the Bells.” I doubt that was the driving force behind the change, but it was a side effect. Now, on Gary’s website, the album on the left is for sale instead of the later “blue” version. Interestingly, the side effect here is that whoever gets the money for sales of that “poinsettia” version does not have to pay mechanical royalties to me because “Christmastime” isn’t on that version. Given this, I think it’s worth noticing that Spotify, iTunes, and other platforms sell only the “poinsettia” version, so . . . no Christmas royalties for me!

O the bells ring and people sing and angel wings are whispering,

“It’s Christmastime”!