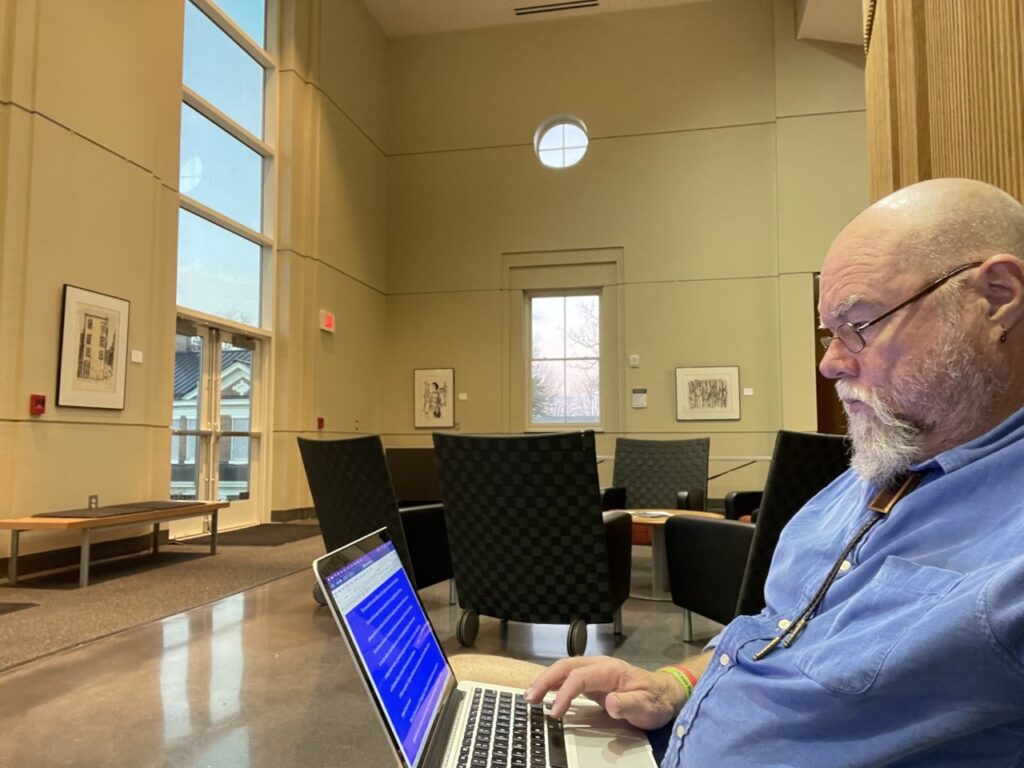

A few years ago (never mind how many), Leesa and I drove to DC to spend a couple of days in the city and take in a Keb’ Mo’ concert while there. Leesa has developed a friendship with Kevin—we get to call him Kevin—over the years (and I’m part of it by proxy), so as is usual for us, we got to go backstage after the show to say hello. As we stood outside his dressing room, Kevin introduced us to his co-star for the evening, who was none other than Taj Mahal. But another less recognizable face was there that evening, and Kevin introduced us to him as well. (Leesa likes to say Kevin introduced us as if we were just as famous as anybody else, which is his generous nature.) That other face belonged to David Brooks, who is a conservative political and cultural commentator whose writing appears often in the New York Times.

Having met Mr. Brooks in that way, I tend to notice his writing when it crosses my field of vision. This past week I saw his name on the NYT Sunday Opinion page. His beautiful essay, which I hope you will read via the link, is titled “How to Stay Sane in Brutalizing Times.” The essay walks us through some “tragic” (in a good way) dispositions of sensibility and mentality, and Brooks summarizes his purpose like this:

I’m trying to describe a dual sensibility—becoming a person who learns humility and prudence from the Athenian tradition, but also audacity, emotional openness and care from the Jerusalem tradition.

His use of the adjective tragic doesn’t seem intended to relate exactly to its meaning in the catastrophes of ancient Greek dramatic tragedy, in which some great hero is ultimately destroyed—or at least brought low—by some fatal flaw such as pride. No, Brooks uses tragic in a less bombastic, less catastrophic sense. What he suggests here is that we look at the world and ourselves in realistic and humble ways, that we live prudently and not arrogantly, that we keep ourselves open to the good and the bad that will come our way and not close ourselves off as being above or beyond the reach of our need and that of others, of relationship, of our humanity in common with all.

One key idea Brooks offers is that our tendency to separate, our increasing tendency to rage, our tendency to dehumanize—desensitize us to the world in which we live. And in our desensitized state, we lose track of the wondrous beauty in nature and in each other. When we could be expanding, growing individually and communally, we are instead contracting into tight balls of rage, anger, and—the root of these—fear.

Such a state of being wadded up tight leaves us unable reach out to others, to feel with and for them, to feel sorry for ourselves for the right reasons such as the joy and fellowship and discovery we’re missing. This also is present in Brooks’s essay, probably nowhere more so than this paragraph:

. . . most people — maybe more than you think — are peace- and love-seeking creatures who are sometimes caught in bad situations. The most practical thing you can do, even in hard times, is to lead with curiosity, lead with respect, work hard to understand the people you might be taught to detest.

This passage, especially its phrase “lead with curiosity,” made me decide to focus this 3rd Saturday Song Story on “Sense of Wonder,” a song I wrote with Mark Chesshir sometime back in the late 1980s. I don’t remember the exact division of labor, but my guess is that Mark wrote most of the music while I wrote most of the words.

Here’s the first verse, sung over an appropriately B-minor chord progression:

A rose, unnoticed, blooms and dies to bloom again—

So many such gifts return to Sender unopened.

Calendar days fly off the wall in whirling wind,

And still the journal lays, blank pages from beginning to end.

Somewhere along my journey to becoming an English professor, I learned that the journal “lies” instead of “lays,” but setting that aside, I like the image of a natural world—embodied in the rose—full of amazing events that fail to amaze us because—busy and distracted—we pay so little attention. I also like the images of the flying calendar days I remember seeing in old TV shows and movies and the journal pages flipping through in the same whirlwind.

Next comes the second section of the first verse:

The treadmill world is small—

No place for standing tall—

Where the heart is a sleeping giant

To be feared and kept tied up.

I’m particularly fond of the image of the heart as like Gulliver among the Lilliputians. Do we fear our hearts and the acts of feeling, caring, and courage they are all capable of leading us into?

The chorus will grow as the song continues. This first chorus is short: “Racing the rain and chased by the thunder, / Hold on to a sense of wonder.” We threw in the “oh-way-oh” to mimic the moaning voices of those working through enslavement and imprisonment.

Here’s the two halves of the second verse:

The spark of childhood put away with childish things

Leaves the good life tasteless and in need of some leavening.

Look to the magic of youth—

The no-holds-barred search for truth.

The heart is a sleeping giant.

Take a chance and wake it up.

Do we take 1 Corinthians 13:11-12 a little too literally? A capacity for joy — a sense of wonder — enriches our lives no matter how old we become. Both positive and negative examples of this are all around us in the people we share family and community with.* One of the ways in which an energetic, youthful sense of wonder can be realized — perhaps the main way — is to “take a chance” and wake up our hearts, unbind them, and let them rise.

The second chorus is longer:

Oh-way-oh — racing the rain and chased by the thunder—

Oh-way-oh — walking the world and stalked by the hunger—

Oh-way-oh — senses dull from the attack they’re under—

Oh-way-oh — hold on to a sense of wonder.

I like these lines. Even more so than back yonder in the 1980s, our senses are constantly under attack, pummeled by media of all kinds and the excessive drama that all of it seems to wield in ever more dangerous ways. Our senses are drowning in information and misinformation “supposed to fire [our] imagination” when it in fact robs us of imagination, one of the main gifts that should be original in each of us.

And yet the rose continues its amazing cycle of life, which is the idea behind the song’s short bridge:

It is not for things to wonder at that we lack

In this catch-as-catch-can struggle with the hourglass.**

We must raise our gaze from our navels (or anybody else’s navel) and take in the world — move through the world — with a sense of wonder.

Sense of Wonder

A rose, unnoticed, blooms and dies to bloom again—

So many such gifts return to Sender unopened.

Calendar days fly off the wall in whirling wind,

And still the journal lays, blank pages from beginning to end.

The treadmill world is small—

No place for standing tall—

Where the heart is a sleeping giant

To be feared and kept tied up.

Oh-way-oh — racing the rain and chased by the thunder—

Oh-way-oh — hold on to a sense of wonder.

The spark of childhood put away with childish things

Leaves the good life tasteless and in need of some leavening.

Look to the magic of youth—

The no-holds-barred search for truth.

The heart is a sleeping giant.

Take a chance and wake it up.

Oh-way-oh — racing the rain and chased by the thunder—

Oh-way-oh — walking the world and stalked by the hunger—

Oh-way-oh — senses dull from the attack they’re under—

Oh-way-oh — hold on to a sense of wonder.

It is not for things to wonder at that we lack

In this catch-as-catch-can struggle with the hourglass.

[The Mark Chesshir lead guitar break!]

Oh-way-oh — racing the rain and chased by the thunder—

Oh-way-oh — walking the world and stalked by the hunger—

Oh-way-oh — senses dull from the attack they’re under—

Oh-way-oh — hold on to a sense of wonder.

*I read something recently that said the old grammatical rule of not ending a sentence with a preposition is on its way out, going the way of the injunction against the split infinitive. I’m giving it a try, but I’m not comfortable with either change.

**Here the phrase “catch-as-catch-can” joins with the second verse’s phrase “no-holds-barred” to reveal my long-held obsession with wrestling as the most apt metaphor for our relationships with the world, with each other, with our faith, with God.