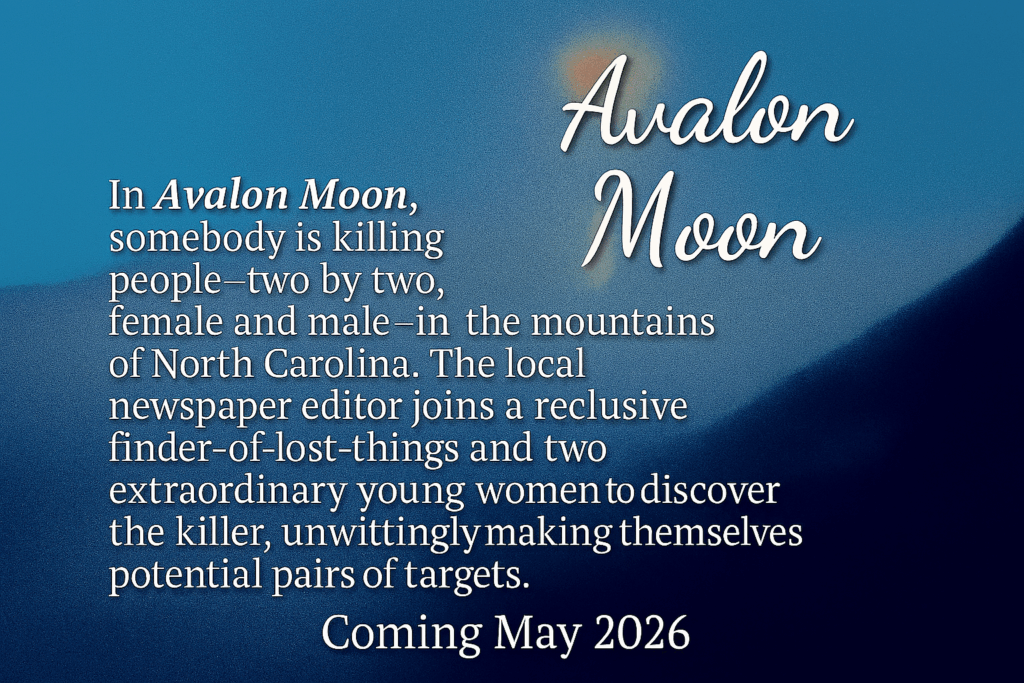

Here’s a little story that I lived recently, and it’s something of a cover reveal for Avalon Moon as well.

Back yonder in the days of COVID, I ran across a Facebook group called “Dark Sire,” which was, as I recall (and as I understood it), connected to a publishing venture devoted to the Gothic, as that term is variously defined.

During the period that Dark Sire was active and I was following along, an artist named Shaun Power regularly posted electronic images of his paintings. (You can check out his work on Instagram at @shaunpower90.) I loved pretty much everything he posted and communicated with him a bit via comments on this piece or that. He was always both generous and appreciative in his responses. His work was most often dark (but rarely monstrous or terrifying) and randomly whimsical. No matter what he posted, far more often than not it resonated with me in some way.

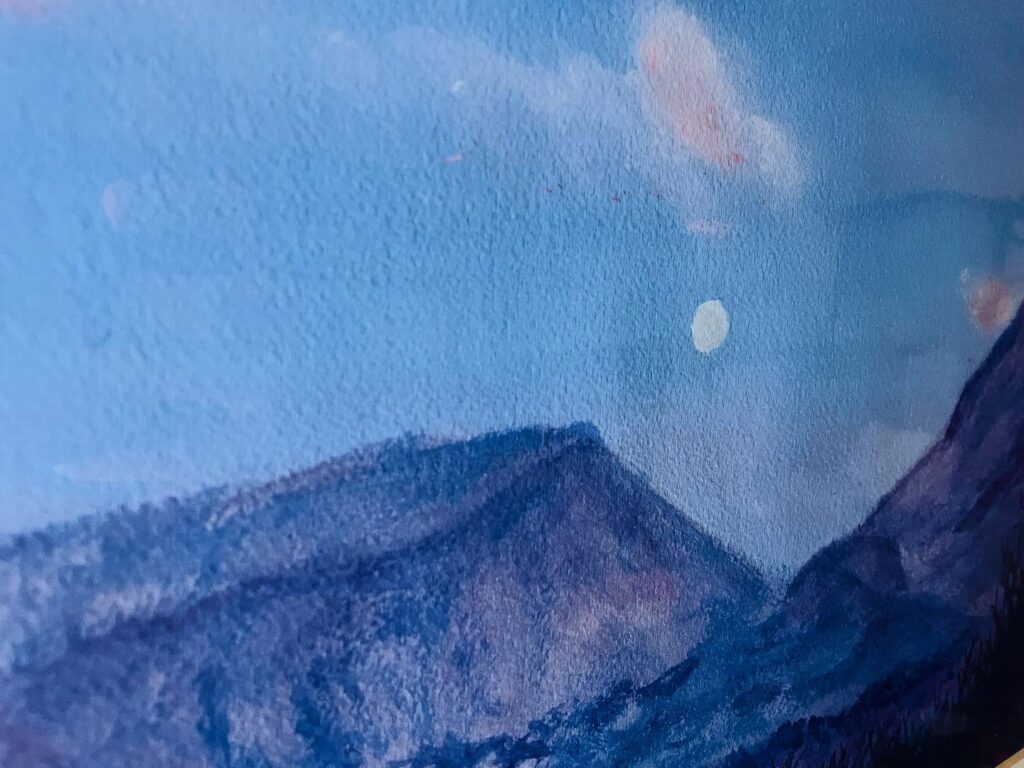

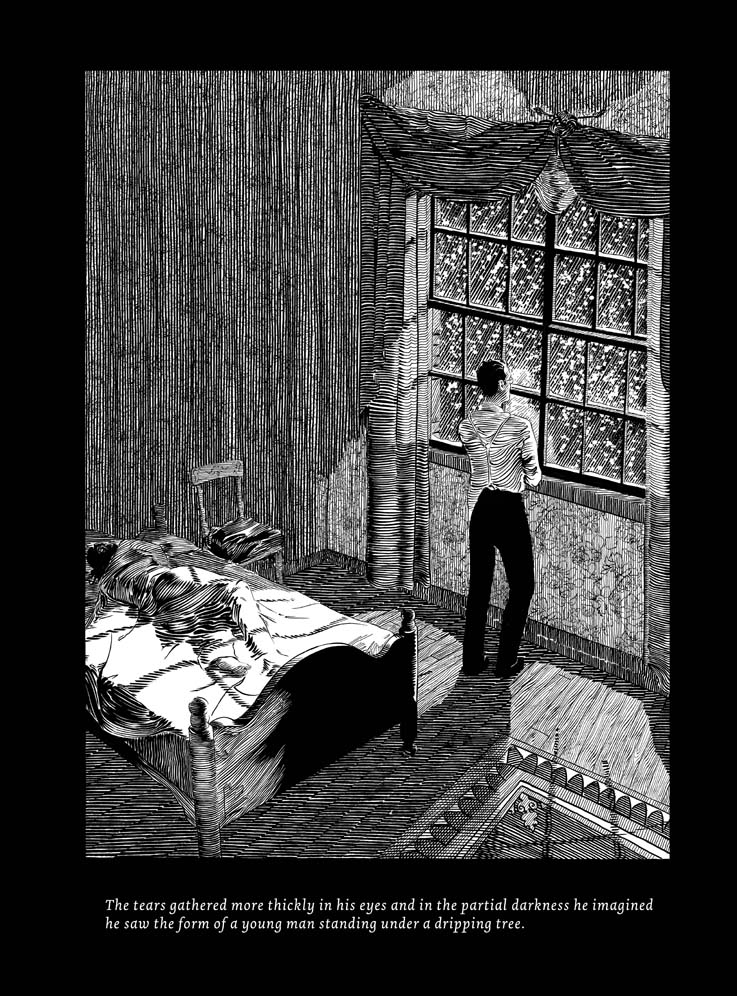

One particular painting appeared in a couple of variations and with a few different names. Here’s the version of it that spoke to me the most:

I don’t remember what title this initially appeared under, but I was immediately taken with it – particular shades of blue that are my favorites, the lonely man with the torch (maybe the torch representing desire, as in “carrying the torch” for somebody or something), the eyes of beasts glowing in the darkness, the human beast that haunts the right side of the image, the haunting silhouette of a woman on the broken branch above the lonely man (possibly what he’s looking for with that torch).

At the time I ran across Shaun’s post of this image, I was somewhere early in the process of drafting Avalon Moon. One character physically absent from the story but still a strong presence is named Kayla Logan Reeves. She’s a painter and an elementary school art teacher. Even though she has disappeared by the time the Avalon Moon story begins, I imagined this as the final canvas she worked on. (You can read about Kayla in her younger days in “Jamboree” and/or listen to the same via her song “Jamboree,” which came before the story.)

Anyway, I was so taken with Shaun Power’s painting that I wrote it into my novel as Kayla’s painting (with a couple of story-related adaptations).

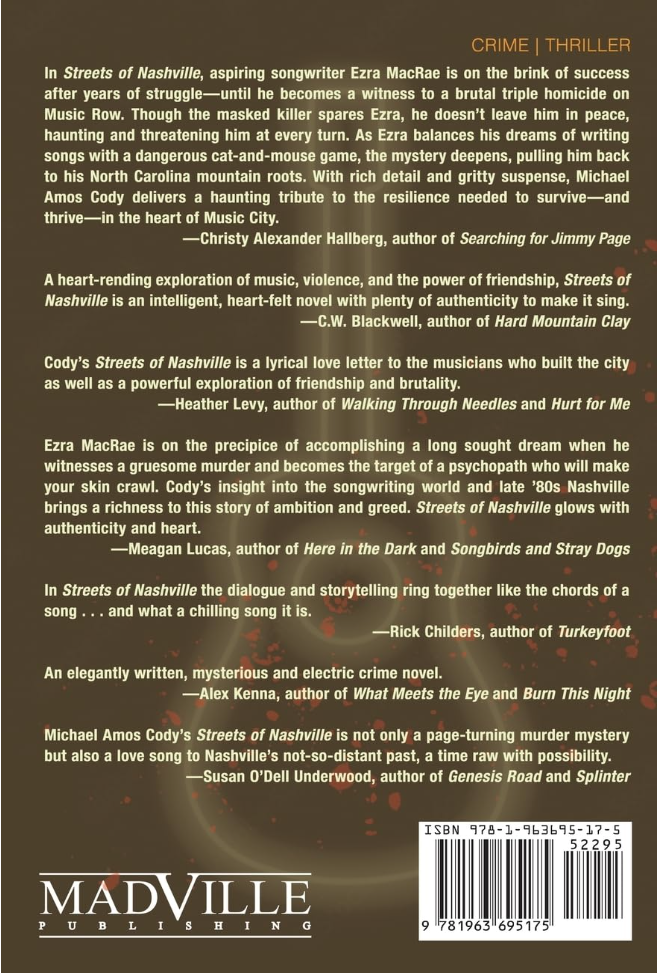

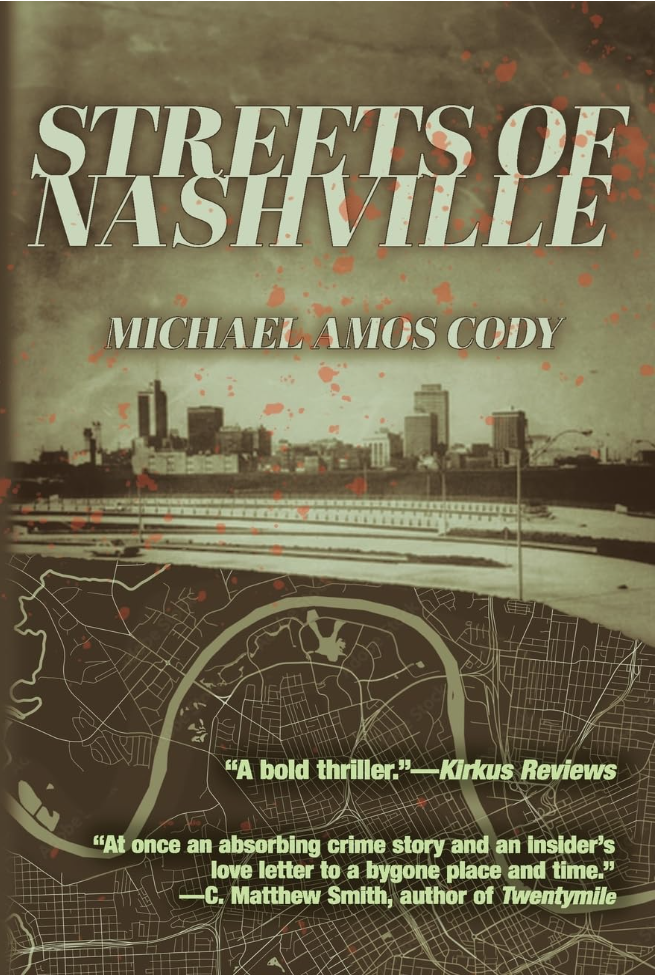

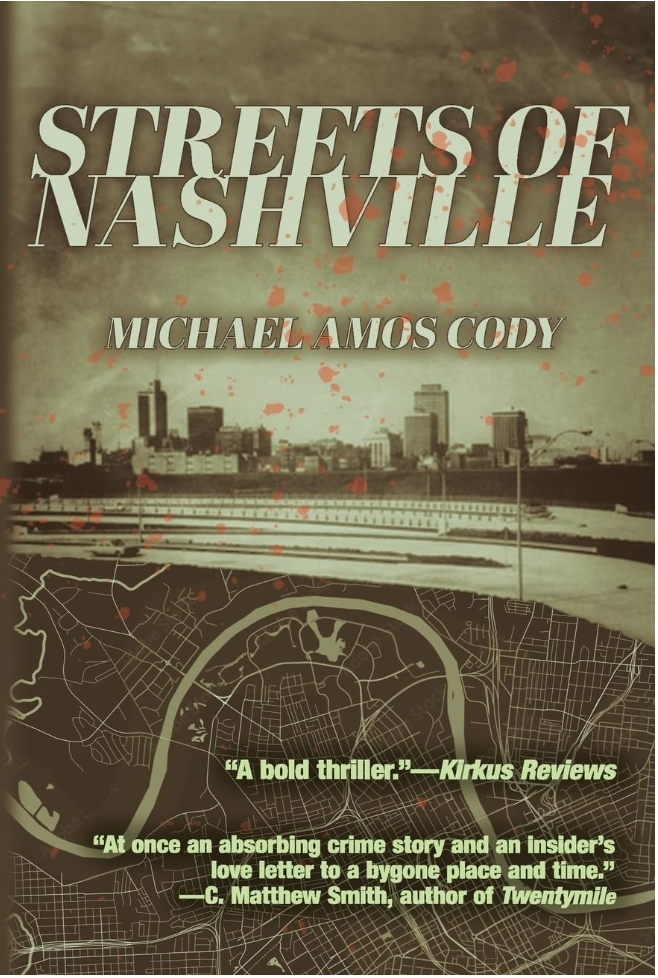

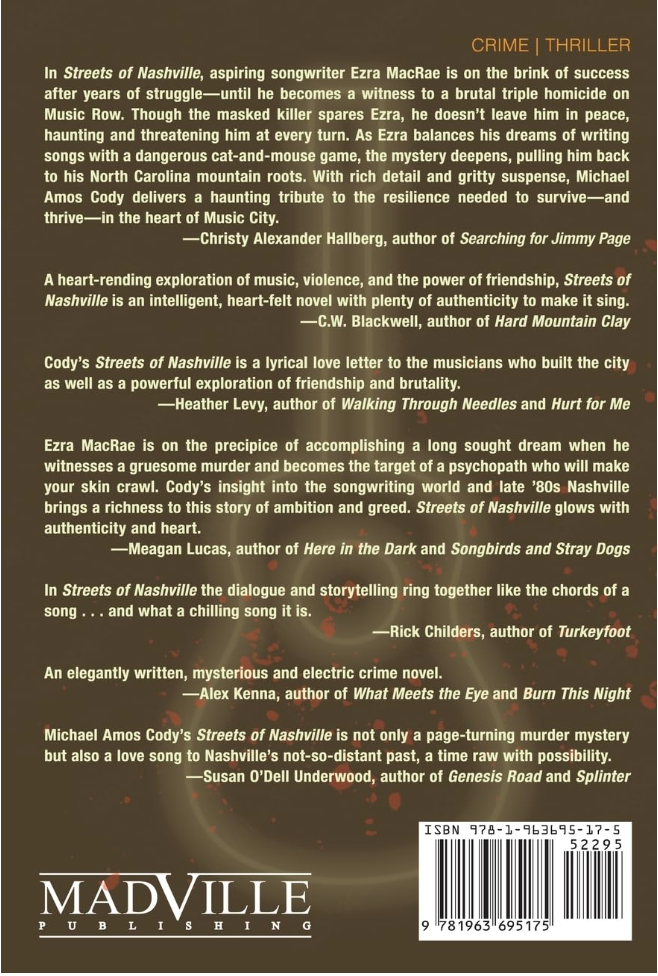

Flash forward to fall 2025 when Madville Publishing emailed to ask if I had any ideas for the cover. I sent a handful of images, one of which was Shaun’s. It’s the one I wanted, and it turned out to be the one Madville liked.

We needed Shaun Power’s permission to use his artwork for my novel’s cover, so I immediately set out (virtually) to track him down. After only a few minutes I learned, sadly, that Shaun had walked on from this world in summer 2024. He was basically the same age I am, only a year or so older, so to learn of his death was made more heartbreaking in that he was so young – as I define young from this vantage point of being sixty-seven years old.

After sitting with that loss for a few minutes, I started looking again, hoping to find next of kin who might be interested in granting permission to use the image. I found his wife, now widowed, and his son, both of whom had points of contact but neither of whom seemed to have a very active online life. I wrote a note to each of them, expressing my condolences for their loss and letting them know of my interest in using one of Shaun’s paintings for my book cover. Given their low-level online activity, I didn’t expect to hear back from either.

But I think it was less that thirty minutes before his son got in touch with me and said that he and his mum thought Shaun would love having his work appear on the cover of Avalon Moon, work he was proud to have shared with Dark Sire. Because Shaun published this image under a couple of different titles, his wife and son asked that we credit it as “Shaun’s Strange Land,” which is a variation of one title he gave it.

I can hardly wait to hold the book in my hands and for others to do so as well – those others include the family and friends of the late great Shaun Power.